Issue: Volume 5, Issue 1

President's Letter

Dr Swapna Bhaskar (President, AFPI Karnataka)

HELLO READERS!

The year 2021 is coming to an end in a few weeks and what we look forward t* in the coming year is t*e hope for a covid free world. The past year has been a mixture of emotional and physical turmoil for *ost of us who were in the forefront of the battle against the dreaded virus. Family physicians played a pivotal role in the country’s victory against the pandemic - which has made the g*vernment, NGOs and public acknowledge and take note of our contributions. Let us keep this momentum going by continuing to keep our patients in good physical and mental health and be their guide through good and bad times.

This year has been very eventful for AFPI Karnataka with various activities throughout the year. The most important of them was our second state conference held in collaboration with the prestigious St John’s Medical College at their campus. The conference was unique in two aspects - the first of its kind hybrid o*e, and the active involvement of

un*ergraduate students from MSA* and SIMSA! The graduation of the second batch of students of St John’s FFM (Fellowship in Family Medicine) in collaboration with AFPI was held at St. John's. The sec*nd batch of graduates f*om the Primary Healthcare Leadership Fellowship run by AFPI with Karuna Trust was held at Karuna Trust's office. The feedbac* from the graduating fellows has been very positive which has resulted in the current year admissions to double from the past year. We were invited by the VC of Rajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences as guest speakers for their monthly webinar on home based COVID management. Dialogues with the University for start of MD – FM programs in other colleges are also being initiated. The motto of the organization in promoting family medicine will be continued through many more such initiatives with the support of our esteemed members.

2022 comes with more events to look forward to – the most important being the 5th FMPC to be held at Hyderabad in February. Please

join our Telangana team and make the event a grand success by your active presence. Also looking forward to get meaningful contributions from all the reader* for our upcoming newsletters in the form of practice anecdotes, research papers, medical news updates and other information that can enhance family practice.

Hope this issue too gives you good insights and thought provoking material. Happy reading!

Issue: Volume 5, Issue 1

Editorial

Akshay S Dinesh (Primary Care Physician)

Experiences in the past many months give me immense confide*ce th*t the leadership crisis

of medical profession in India is on the path

to resolution. It is through reimagining primary healthcare as a field and the various roles of healthcare workers that we will get there.

Klaus, et al describes the roles of family

physicia* as :

-

Care provider

Care provider -

Consultant

Consultant -

Capacity builder

Capacity builder -

Clinical trainer

Clinical trainer -

Clinical governance leader

Clinical governance leader -

Champion of community-orientated primary care (COPC)

Champion of community-orientated primary care (COPC)

We have seen exemplary leadership all around us. During times of crisis our ability to resist and sustain have been directly related to the amount of leadership embedded among

us. But we have to be critical of ourselves and ask whether we have been able to systematically harness our leadership potential to its maximum. When we train individuals, are we making them highly autonomous and capable of performing as leaders? When we build systems, do we create space for growth and emergence of new leaders?

That is where the family physician's role as more than just a care provider atta*ns utmost signficance. Today, the family physician is presented with a huge responsibility - that of fixing the system of healthcare. How do we drive down inequities in healthcare and drive up the qua*ity and compreh*nsiveness of our healthcare? How do we rebuild trust between the public health system and the citizens? Where do we see ourselves in the next decade and the next pandemic?

We are on the cusp of a transformation. The world now realizes that "l*t us fix the problem when it hits us in the face" is not an attitude that can save us from massive

problems that come unannounced. There is universal acceptance that health infrastructure can't be built overnight. Individuals and organizatio*s everywhere are turning their focus towards fixing this once and for all. What we do today will decide how big of a transf*rmation we are able to bring.

This newsletter issue ha* many inspiring articles. But it is incomplete. It hasn't heard your inspiring story. What transformation are you bringing? What do you want the world to hear about? Let us use this space to inspire each other to perform to their fullest.

-

1. Kumar, Raman1, The leadership crisis of medical profession in India, Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care: Apr– Jun 2015 - Volume 4 - Issue 2 - p 159-161 https://doi.org/10.4103/2249-4863.154621 ↩

-

2. von Pressentin, K.B., Mash, R.J., Baldwin-Ragaven, L. et al. The perceived impact of family physicians on the district health system in South Africa: a cross- sectional survey. BMC Fam Pract 19, 24 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875- 018-0710-0↩

Issue: Volume 5, Issue 1

AFPI Karnata*a Activities - 2 021

-

1. Conducted the first CME on “FINANCIAL PRESCRIPTION FOR WEALTH MANAGEMENT” ON 24-2-2021. Ms PREETHI LODAYA – financial advisor and founder – redwood financial Services spoke about the basics of finance management for doctors. The webinar was attended by doctors from India and abroad. Many expressed interest for continued sessions on similar topics in future.

-

2. On the International Woman’s’ Day – March 8, 2021, we released a short video on “Menopause – a phase of life” by Dr Swapna Bhaskar on the youtube channel – AFPI KARNATAKA – For public vie*ing.

-

3. The second webinar was conducted on 1* Th March 2021 on the topic – “SWEET PREGNANCY: Case based discussion on gestational diabetes”. Dr Shalini Chandan was the speaker and Dr Anupama Menon moderated the session.

-

4. On 21 March 2021- released the next video on – “COVID VACCINES – AWARENESS FOR GENERAL PUBLIC “done by Dr Swapna Bhaskar. The video gathered more than 1.4 k views within a week of release.

-

5. Released a short video on World TB day - March 24. The theme of this year was “THE CLOCK IS TICKING, ITS TIME TO END TB”.

-

6. Another video on “Right method of using inhalers” by Dr Kritika Ganesh – was released in April on the YouTube channel of AFPI Karnataka.

-

7. Webinar on “Medico legal Awareness in the current era” was conducted on 11-6-2021. Eminent medico legal experts Dr Naresh chawla and Dr Divya HM spoke on case based scenarios of *eneral practice and highlighted on the do and don’ts to prevent and tackle legal issues in practice.

-

8. The valedictory function of the second batch of FFM (Fellowship in FM) students from St John’s Medical College was held on August 7 2021. Dr B C Rao, Dr Mohan Kubendra, Dr RK Prasad, Dr John D Souza and other dignitaries presided over the function. The role of AFPI in conducting the program was highly appreciated by the team of St John’s. The importance of FM in the pandemic was stressed upon by the speakers.

-

9. THE SECOND STATE CONFERENCE – AFPICON 2021 was held in collaborat*on with the family medicine dept of St John’s Medical college at the lecture hall – 1, Medical college Building on October 3 , 2021. The theme of the conference was **“NEUROPSYCHAITRY IN POST COVID PRIMA*Y CARE” and the punch line was “PRIMARY CARE IN THE NEW NORMAL”. It was

a unique hybrid conference with more than 200 participants from all over India. Dr Yogesh Jain gave the guest lecture on “Inequity in healthcare during Covid and how family physicians can bridge the gap “. Fr Paul Parathazham - Medical Directo* of St John’s National Academy of medical sciences , Dr George D Souza- Dean of St John’s Medical College and Dr Raman Kumar – National President AFPI were guest of honour for the inaugural function . 31 posters were pr*sented by delegates and cash prizes were given to winners. The conference also saw active participation from medical students of MSAI and S*MSA – the first of its kind.

10. The graduation ceremony of the second batch of Primary Health Care Leadership Fellowship by AFPI and Karuna Trust was conducted on 29 October at the Karuna Trust Premises. Five doctors obtained the fellowsh*p this year and the coming year has an enrolment of 7 aspiring primary care physicians. Dr Sudarshan, Dr B C Rao, Dr Swapna Bhaskar, Dr RK Prasad, Dr Soumya Vivek, Dr Jyotika Gupta, Dr Akshay S Dinesh, Dr Dwijavanthi Kumar (online), and

Dr Swathi S B (online) presided over the function. AFPI is looking to upscale t*e program by involving more faculty and continued training in broader aspects of primary care.

Issue: Vol*me 5, Issue 1

COVID Diaries

Dr Devashish Saini (Family Physician and Founder, Ross Clinics, Gurgaon)

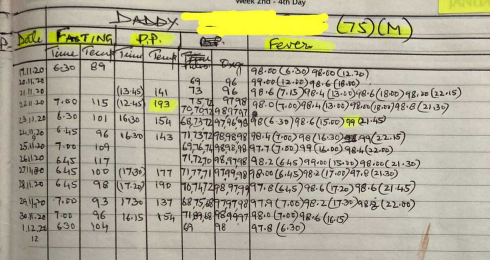

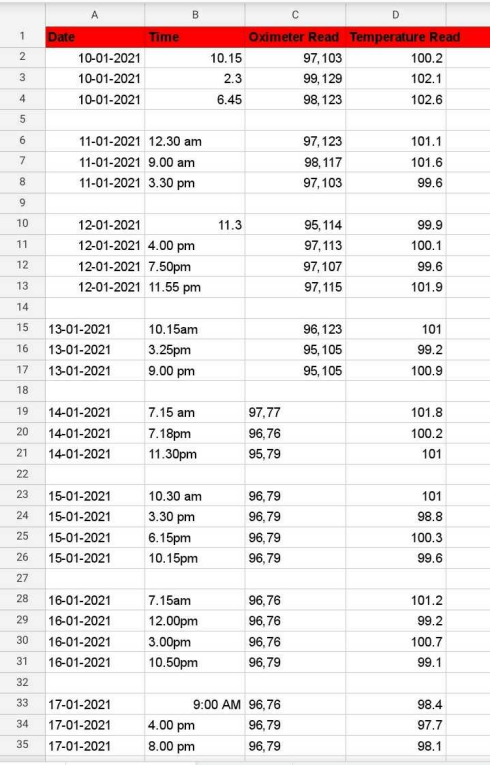

I often ask my patients to record their measurements at home in a diary, and bring them to the next app*intment. I find that this improves the self-efficacy of the patients and their family members in taking care of their illnesses, and helps us doctors take better care of them! At the same time it's an ideal, and reality loves to wash away our best laid plans

Some patients do check their parameters, some don't. Some of those patients w*o do go to the trouble of measuring them regularly, may not record them! And those who diligently record them may forget to bring those readings when they come for a follow- up consultation! And *ome of those who keep meticulous records, stop after a few months.

I often tell my patients, "Your proper treatment will only start when you start maintaining a record, till then we're just playing with your illness!" And truly, the home record is vital in adequately managing Hypertension and Diabetes Mellitus, and I've

found it useful in other illnesses too, like Typhoid fever, and Food allergies.

I keep *ondering how to inspire patients and family members to keep better records. I think I got some answers last year

All of us battled the pan*emic in the last 12 months in our own way. And as we did, we and our patients became more comfortab*e with and attached to our gadgets. And I'* not just talking about the comfort of attending Zoom meetings in pyjamas! Even taking care of COVID patients at home was different than expected, with technology at our service

Most patients of COVID-19 recover without any complications. However, some patients, even without co-existing illnes*es, do end up getting complications, and such patients can deteriorate very rapidly. So it's vital for the patients or their family members to regularly measure their vital signs, especially temperat*re and oxygen levels, and share with the doctor once a day.

So, during the first teleconsul*ation with a patient with a positive COVID test, towards the end I would give them instructions to measure their Temperature, Pulse *ate, and SpO2 three times a day, and record them on a piece of paper, and share with me once a day (and *eport imm*diately if SpO2 less than 95*). I would also write these instructions in the prescription.

I hoped that since the follow-up was going to happen *ver WhatsApp chat or video, it would be easier to *et to the readings! I took ca*e of about 200 COVID-19 patients, and it was an interesting experience to see the different ways in which they interpreted the above instructions, and followed them, each in their own unique way!

There were of course some patients who steadfastly ignored these instructions, and did not share even a single reading. One patient didn't even buy a Pulse oximeter! Ironically, these were the same patients who got expensive Corona Panel tests done, at the suggestion of family and friends, and forwarded them to me for interpretation. So probably the cost of the Puls* oximeter was not an issue.

Some others insisted on saying their parameters were normal, and because they were normal they didn't note them down! I wish there was an easy way to explain to such patients why doctors need to see normal figures too, without getting into confidence intervals, trends, high-normal, etc I trie* telling them that normal figures make doctors happy, please record them for our happiness! This seemed to work for some patients

To balanc* out such patients were those who measured their parameters 20-30 times a day, and concernedly reported when the oxygen levels dropped from 98% to 96%, or the heart rate rose from 72 to 84 per minute! Many an hour was spent as a counsellor *o listen empathetically, explain gently the normal ranges, and calm dow* their ruffled feathers

Now coming to the "normal" minority, who followed the instructions obediently! The records that they shared ranged from too simple to too co*plicated! Some used paper and sent me screenshots, some sent W*atsApp texts, and one even gave me access to his Google Sheet of vital signs!

Some patients were good at giving structure to their records, noting do*n the date, the time, the nu*bers, and the units, one record in one l*ne. If there were multiple family members, each person's name, age and sex was clearly mentioned on top. Enough to bring a tear of joy to the doctor's eye! I happily shared such beautiful records with other patients as examples of how to do this best!

Some patients just sent the numbers, without any date or time, or even whether that 84 on their record was pulse rate or oxygen *evel! This led to some skipped beats on the part of the doctor, and a call or two to finally cla*ify,

that 84 was indeed the pulse rate and the oxygen level was a very relaxable 98%!

All in all, it was just like asking pa*ients to drink more water or to take frequent breaks from prolonged sitting. Recording and sharing of measurements is just another behaviour change that we want from our patients, and each patient is on their own journey, from Contemplation to Planning to Action and Maintenance. As doctors, all we can do is gently nudge them to t*e next stage, and build their self-efficacy to avoid relapses and continue the progress!

I woul* like to believe that with every patient, I learnt something more about record keeping itself, about how to give complicated instructions in simple language, about empathetic counselling, and I feel I am now better equipped to get patients to monitor their health regularly. Of course, I'm sure the next patient will throw up a bigger challenge, as they always do, to keep us always on our toes!

Issue: Volume 5, Issue 1 Practice Experience

Dilemmas of a GP (Case 2 )

Dr Swapna Bhaskar (President - AFPI Karnataka; HOD - Family medicine, St. Philomena's Hospital)

How and when should we cut down an extended co*sultation?

A young man walks in with his wife into my clinic one night jumping the queue saying he is very sick, running very high fever and is too tired to wait. Although I see patients with appointment only, these kinds of walk-in ill patients are let in by my receptionist with a warning that they do not have an appointment and are replacing another patient’s time*

He definitely looked sick and dehydrated (unlike quite a few who come with “supra- cortical” illnesses) , had a temperature of 104.8 degree fahrenheit, low BP, but did not have any particular *ocus of infection. He gave a past history of vitamin D and B12 deficiency but had stopped treatment a few weeks ago.

Since it was the dengue season in Bangalore and wanting to rule out other infections too – I advised for a preferable admission and worked up for the routine infections. Meanwhile I started noticing that his wife was constantly interrupting the consultation talking about her Vit*min B12 deficiency, her sister’s deficiency and how different the symptoms were for each of them. I did give him a paracetamol injection which I load and give myself as my small clinic does not have a trained nurse for it. Overall the consultation was overshooting the normal stipulated time which started making me a little restless by now.

Denying my advice for admission, the patient said he will get the investigations done and review. He slowly walked out of t*e clinic for payment but his wife wasn’t ready to go. And to my dismay she started asking about the lesions on her lips since 2 weeks (herpes l*bialis), the reasons for it and what she could do to alleviate it!

As a GP now my dilemmas crop up –

-

1. How to manage such “buy one get one” consultations? That too during a busy OP?

-

2. The young lady very well knows that she has come in another patient’s time slot and has seen the queue of patients outside.

Still she deems it appropriate to discuss trivial issues. Can we cut short *uch statements without hurting their sentiments and losing our temper?

-

3. How can a GP be “po*itely strict “ with the patient ?

Issue: Vo*ume 5, Issue 1

Choose Primary Health Care: An address to young medical students and doctors

Dr Pavitra Mohan (Co-founder, Basic HealthCare Services)

I was invited to speak to medical students of Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences, located in Wardha, part of the Reorientation of Medical Education p*ogram.

I spoke on choosing primary healthcare as a career and life choice. I was overjoyed at the interest, understanding and deep concern for India's inequitable healthcare system among the students. If physicians are indeed "attorneys of the poor", I saw many attorneys in that room. That filled me with an unbearable hope.

Here is an excerpt of my address.

Hello dear students and friends,

I am so happy to be speaking to you today. Besides the joy of speaking to young students of a medical college that promotes a culture of service among its medical students, I have another important reason to be happy.

My own desire to get in Wardha Medical College

Thirty-six years ago, I was *reparing to get admission to a medical college. And since MGIMS had its own medical entrance exam, I was preparing for it separately. One of the paper that you needed to clear for getting admission in MGIMS was Gandhia* Thoughts. I read through Gandhi’s autobiography and decided *his is where I really want to study medicine. In the exams, I did well in Gandhian thoughts, but flunked in Biology! My dreams for studying in MGIMS shattered – I did study medicine though. I am therefore happy that I am speaking to students of the medical college, where I dreamt of studying, but failed to get admission!

Working in Delhi, exposure to misery and illness, and magic of modern medicine

Subsequently, I studied and worked at government hospitals in Delhi during my MBBS and MD, where I was getting exposed to realities of harsh lives that so many people lived. When they came to the hospital, they would be in tatters, no money in their pockets and no food in their bellies. Children would die of neonatal tetanus and measles.

However, I also learnt the beauty and magic of modern medicine: we could still snatch the kids out of jaws of deaths. Antimalarials would be magical, so would the correct treatment of Nephrotic Syndrome.

Udaipur, exposure t* rural areas and advice

After my MD, I got an opportunity to live and work in Udaipur, at RNT Medical College, as a faculty in Paediatrics. At Udaipur, for the first time, I saw a real village, and understood how rural administration and health systems work.

However, I was still seeing much deaths, much misery among children and their families who would come to the hospital. While some would be treated, many others, I would realize would still fall ill again, return to the hospital again, as they had nothing to eat or no one to care.

Frustrated, I went to my mentor professor MK Bhan, one of the most beloved paedia*ricians and public health researchers that country has produced. He listened to me and then said “first get trained in public

health, then we will speak”. I did take it seriously and took a year off to pursue MPH. It opened up new world for me, new skills, new perspectives.

UNICEF and exposure to realities of healthcare in remotest areas

During my stint at UNICEF in Rajasthan and Delhi – I was heading the child health and health systems work of UNICEF India Country Office, I would visit the remotest areas of India, where I found that our health services do not reach. No one reaches.

A large population, tribals, dalits etc are left to fend for themselves. They do not have the money and means to seek healthcare, and when they do, high costs and indifferent, almost hos*ile behaviour they receive make them poorer.

That rankled me. W*atever we did at national or state level does not reach these populations. I realized that there are no easy answers, and solutions would lie in actually jumping in the field and finding answers.

Dilemma: Clinical care and public health

When I was a clinician I was happy that I could save lives: I was able to save lives of many children due to severe malaria, diarrhea, newborn sepsis, tuberculosis,

nephrotic syndrome. However, I was frustrated by the fact that many diseases I saw in ch*ldren had social origins. When I saw child die of measles, I would th*nk why did she not receive a simple inexpensive vaccine? Th*t drove me towards public health* I wanted that I should spend my time and energy not in treating one child at a time, but should be able to improve health of the communities. It was a mana*ement problem to be fixed.

When I studied and researched public health, I *as happy that I was able to influence health of the populations: when I led t*e health program* of UN*CEF in Rajasthan, with some effective planning and execution, childhood immunization coverage in the state increased from 24% to 48% in four years- time. I presume that would have led to saving lives of thousands of children.

Social *nd political milieu affects health

However, I realized that why some people are healthy and some are not does not depend on new new drugs or new vaccines or because we did not know how to manage programs. It depends on social and economic inequities. No one cares for the poor populations, I le*rnt. For example, I found out from a research that a simple health service such as immunization is provided far from where poor peopl* live, making it difficult for them to access. If it was an equitable world, health services would be closer to those who need it the most.

I also found that when people from under- privileged castes would reach a health facility, they would be treated poorly, shabbily. When we took over a Primary Health Center from government, people from so called higher castes would barge in the OPD, as if it was their entitlement to be seen before everyone else. Those from under- privileged families would keep waiting, as if this was their destiny. If after five years of running this PHC, there is one thing I am proud of, it is that we have changed that. It is first come, first serve. NO privileges, no preferences.

Anyway, that led me to pursuit *f origin of these inequities. I understood how the cutting of jungles for economic gains and centuries of exploitation by privileged castes have led to food insecurity, and scarcity of water in the tribal areas, leading to rampant malnutrition and disease. It is not because people did not know what to eat: if they did not, civilization would not have survived for thousands of years. Such an understanding led me to explore social sciences and economy and politics.

All these perspectives: clinical, public health and socio-political were correct, when looked in isolation. Modern medicine could treat people and alleviate their suffering; effective public health programs could save thousands of lives, and addressing the social and political arrangements would correct historical inequities.

Primary healthcare is one discipline where *ublic health, clinical care

and social development merges beautifully.

Where does one begin then? Primary healthcare seemed to me to be the best fit.

We set up AMRIT Clinics in remote, rura* and tribal areas of South Rajasthan. They provide preventive, promotive and curative care. We co*duct relevant research and we advocate for more responsive health systems for the poor.

Primary healthcare is healthcare of the people, for the people and by the people. It is no coincidence that democracy has the same definition, replace healthcare by government.

Primary healthcare system provides preventive, promotive, curative and rehabilitative care. It uses evidence based care. It does not frag*ent a patient into different systems but looks at a person as a while, in context of his or her family and community. It tries to understand and address social (and political) determinants of health*

Here I seemed to have found a path; that integrates clinical medicine, public health and social development.

Primary Clinical care is exciting because it looks at the patient a* a whole and does not f*agment him or her into different systems. For example, a person with TB has malnutrition. Family would have needs for food, and maybe a single woman who needs connect with the pension.

It is evidence based so you need to keep reviewing scientific evidence: for example, few years ago, there was a conclusive evidence that Tranexamic acid helps in managing PPH. Or that community KMC hel*s in reducing deaths among LBWs.

It requires clinical courage, how else would you deliv*r a primi with breech with five grams haemoglobin with no place to refer to? It requires a deep understanding of communities and their customs, other*ise how would you manage a situation where the customs do not allow you to conduct a childbirth, which is considered to be polluting in front of a temple?

It requires understanding and engaging communities in their own health, and development.

It require* understanding of public health to prevent and manage malaria epidemic in your community. It requires understanding and addressing social determinants: to promote food security for example.

And finally, it requires addressing political determinants and raise you* voice, using your credibility and grounded understanding, to raise voice against social injustice. Why don’t health centers fun*tion in areas where marginalized people live?

Myths associated with primary healthcare

There are several myths associated with primary healthcare.

Firstly, that primary healthcare means managing a few priority or simple illnesses. It is farthest from truth. In primary health care clinics that we run, nurses and young physicians treat anything from diarrhea, severe malaria, diabetic ketoac*dosis, rheumatoid arthritis to deli*ering a primi with breech.

Second, and a related myth is that providing primary hea*thcare requires m*ch less skills than a specialist or a super-s*ecialist (the term supe*-specialist is used only in India* everywhere else it is called sub-specialist!). An absolute lie. You require knowledge and skills of different kinds, and have to be ingenious as you have to really apply all your knowledge and skills. Also a range of social s*ills, since you are embedded in the community. And management skills.

Another one, (I find new lies peddled from time to time), that primary healthcare is less effective than specialised care. Several studies have confirmed that counties with strongly evolved primary healthcare systems have much better health outcomes (at a lower cost), than those which have strong primary healthcare systems.

Specialising in primary healthcare

You are an inferior doctor if you are not a “specialist” of some kin*. You can of c*urse

“specialise” in community medicine, public heal*h or family medicine. And spend months and years in practicing primary healthcare in different settings. A travel fellowship convened by Tribal Health Initiative offers that opportunity.

My own journey and joy

I have enjoyed every moment of my journey in primary healthcare in rural areas for last ten years –a p*oof I have spent ten straight years without looking back. I had never spent more than five years in one job before that!

I have grown as a person because I got enormous opportunities to love and be loved, by the patients, by community members and colleagues. Every day, I am moved, and challenged to do more. I have honed up my clinical skills, have built some lovely networks, and have conducted some relevant research.

Our organization has hosted some wonderful young people, with wonder in their eyes in fire in their bellies. Some have stayed back and others hav* moved on to do more work in more areas that need it. And we travel to work among beautiful jungles, ponds, waterfalls and sunsets.

With my own experience I can say that primary healthcare is a wonderful, joyous, glamorous and wholesome option *or young medical graduates like yourselves. A path to grow, soar and serve.

Lots of luck and blessings for your future!

Issue: Volume 5, Issue 1

Back Bencher: A view of life and continuing medical education from the back benches

Dr B C Rao (Mentor, AFPI Karnataka)

I am comfortable sitting at the back in any function, be it a continuing education meeting, a wedding reception or a civic get together. This habit I acquired some 50 years back in medical school. Then it gave me an opportunity to unobtrusively leave the hall through the large french windows placed strategically on the sides of the lecture hall. Those days the lecturers if they noticed one’s absence, took no off*nce.

This habit has stood me in good stead and give* me ample opportunity to leave mi*way without offending the speaker *r the organizers. On rare occasions, when I had to don the mantle of a speaker I keep a subtle watch on the back rows to see if any one leaving midway, a sure sign of *oredom/ inattention. I am rather fortunate that it has not happened often.

In those bygone days, the continuing education programs were simple affairs with a lunch or high tea thrown in at the beginning or at the end. The speakers mostly depended

on memory and experience and spoke extempore. Naturally some of them bored us to death. Then too being a back-chair occupier came in handy to take unobtrusive leave.

Has the advent of advanced audiovisual aids motivated me to occupy front seats? Sadly no. I find it has made matters worse. The modern-day speakers, with rare exception*, have taken to reading these projected slides and not really addressing the audience. Droning voice combined with dimmed lighting is conducive to sleep and it's with difficulty that I keep my head up and eyes open. This goes unnoticed if you are a back seater. When I compare the speakers of yesteryears to the present ones the ones of the past get a higher score. May be, being old myself, I may be biased. I remember vividly my Neu*ology teacher professor late M.K Mani miming grand mal and petite mal (now the modern neurologists have named these differently) while speaking on epilepsy. Similarly, I remember another M.K Mani (

great teacher, alive and kicking) speaking on hypertension, though with the help of slides but hardly looking at them.

Lately I am facing a piqu*nt situation. Thanks to my seniority and mop of grey hair, I am easily spotted and given our penchant for recognizing (respecting?) old age, I am forcefully escorted to the front row of chairs to my discomfort. Here again there's is some hierarchical distinction. The front most row is generally is a row of cushioned sofas or well- padded chairs meant for VIPs and thankfully the organizers have not recognized me as one and they usually make me sit behind these.

The front row occupants *enerally come late and the importance is based on the position they hold rather than to any achievement academic or otherwise. Needless to say, by arriving late, they also hold up the proceedings. In one such meeting a serving police official of ill reput* was the chief guest in a professional function. I felt happy that I was not in that front row sitting with this worthy.

It's a different matter in social functions like weddings and receptions. Being the family doctor for generations of families, I often get invited to many of these which even includes ceremonies associated with death. Often, I have the dubious distinction of having presided over these deaths. Readers should not get the impression tha* I am another Dr Herold Shipman [who killed many an elderly]. In my case these patients who died under my care at home were terminally ill and I saw to it that unnecessary

hospitalization and the *e*ulting expense were avoided. Weddings however *re joyous occasions. Normally I try and avoid the*e ostentatious and wasteful ceremonies. But sometimes I have to attend as the families concerned are too close for me to no* to.

Recently I went to a wedding. The *irl, a third-generation patient, I have known since her birth. She is now placed in the US and the young man; her groo* is a German. The girl’s father and mother and the grandparents from both sides also are/were my patients.

Both the grandfathers are dead (*nder my care at home), but the ailing grandmothers pushing 80 are very much alive. So this intimate relationship made it impossible to avoid this wedding.

The simple wedding ceremony was over and the time arrived to bless the couple. Normally the elders of both sides take the first honor followed by other relatives and friends. In this wedding* this tradition was br*ken and I was ceremoniously escorted to the platform where the bride and groom sat and was requested to initiate the process. It must be a spectacle to the well-dressed gathering to see this chappal clad, shirt and trouser wearing, nondescript old person belonging to another caste and community, being escorted to initiate *he holy process.

This kind of affection, respect and love makes us family physicians feel that we made the right choice in choosing this branch of medicine.

Issue: Volume 5, Issue 1

Essential oils with pro-convulsive effects: Are physicians and patients aware?

Dr Thomas Mathew MD, DNB, DM (Professor and Head, Department of Neurology, St John’s Medical College Hospital, Bengaluru)

Essential oils are not ess*ntial to humans but are essence or concentrates of plants or plant parts. Esse*tial oils of various plants can have pro-convulsive effects. Notable among them are eucalyptus and camphor. Camphor and eucalyptus oil have been implicated as a cause of seizure, epilepsy, migraine and cluster headache. Both camphor and eucalyptus contain 1-8 cineole, a monoterpene, which has been proved in animal models to be epileptogenic. These essential oils are commonly present in various over the counter balms and oils and are often used by people for common ailments like headache, common cold and backache.

A group of neurologists from three majo* hospitals in Bangalore, south India described 10 cases of eucalyptus oil inhalation induced

seizures. They als* published a paper on

Essential Oil Related Seizures due to balms and various preparations containing the mixture of essential oils of eucalyptus and

camphor in the recently in the journal

epilepsy research. They observed that many

of the cases of the so called “idiopathic seizu**s” are indeed induced and provoked by essential oils of eucalyptus and camphor* In their case series it wa* found that inhalation, ingestion and even topical application can trigger seizure. Surprisingly the commonest mode of exposure was topical application on the fore head, face and neck. Physicians who are not aware of the pro-convulsant properties of these e*sential oils, rarely enquire about the exposure to the*e in their history taking. They may falsely treat an essential oil induced seizure as idiopathic seizure. Essential oil exposure also is an important cause of break through seizures. If you do not identify the true cause, patients may be falsely labeled as “refractory seizure.”

A survey of the literature shows essential oils

of 11 plants to be powerful convulsants. The

essential oils with pro-convulsant effects are eucalyptus, camphor, fennel, hyssop,

pennyroyal, rosemary, sage, savin, tansy, thuja, turpentine, and wormwood. They contain highly r*active mon*terpene ketones, such as cineole, pinocampho*e, thujone, pulegone, sabinylacetate and fenchone. Camphor is a known convulsant for the past 500 years and was used to be given both orally and by injection to tr*at schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Common over-the- counter medications which cont*i* the essential oils of eucalyptus and camphor are Vicks, Amrutanjan, Tiger Balm, Zandu balm, Axe oil, Olbas oil, Equate etc. These herbal products tend to be used and quite often abused to treat common ailments such as cold and headache by both the people with epilepsy and general public, who are oblivious to the epileptogenic effects of these products. People often use them thi*king they are natural and safe. People also presume topical applic*tions do not result in systemic absorption. It is high time that public especially those with seizure and epilepsy should be counseled to avoid these preparations which contain essential oils with pro-conv*lsant properties. These cases of essential oil related seizures should sensitize commercial companies and regulatory authorities to put labels on products with pro- convulsant essential oils *tating “potentially pro-convulsant and to be avoided by people with epilepsy”. This may prevent many cases of essential oil related seizures espe*ially those sec*ndary to usage of camphor and eucalyptus.

The researchers have classified essential oil related seizures into Essential Oil Induced Seizures (seizure primarily caused by

essential oil exposure) and Essential Oil Provoke* Seizures (break through seizure in a known case *f epilepsy). Without the necessary knowledge of the epileptogenic potential of the essential oils, these cases would have been misdiagnosed as idiopathic seizures and the usage of these potentially deleterious produ*ts would have gone unnoticed if not for specific inquiry regarding their usage. Most physicians in the world do not check for exposure to eucalyptus oil or camphor for the lack of mention in textbooks of medicine and neurology. Oblivious *o the epileptogenic nature of these essential oils, the patients would have continued to use them, possibly causing their seizures to worsen and prove to be refractor* to prophylactic treatment. *he proportion of seizures resulting from preventable e*posure to eucalyptus oil and camphor is unknown. However, a significant amount of seizure burden and unnecessary anti-epileptic treatment, which carries side-effects, may be prevented by spreading awareness about the epileptogenic potential of these substances. Essential oil related seizures may turn out to be the most unrecognized preventable cause of seizure. Essential oils are also implic*ted

in worsening migraine. In case report

recently published, a 14-year-old boy with chronic daily headache of 1-year duration, refractory to four antimigraine drugs, was found to be using a balm called Amruthanjan (10% camphor and 14.5% eucalyptus) daily on his forehead to relieve headache. Patient had complete relief of headache within 2 weeks of stopping the balm application. All his anti-migraine drugs were tapered and stopped over a period of 3 months. At 1-year

follow-up, he was headache free. Essential oils containing tooth pastes are recently been implicated in causing cluster attacks. Two cases were reported and in one the cluster attack was precipitated by re-challenge with the same tooth paste.

More studies are needed to be done in this fie*d. But till then, it will be prudent to enquire about exp*su*e to these pro- convulsant essential oils in all patients with migraine and clusterheadaches.

-

1. Thomas Mathew, Vikram Kamath, R Shivakumar, Meghana Srinivas, Prar*hana Hareesh, Rakesh Jadav, Sreekanta Swam*. Eucalyptus oil inhalation– induced seizure: A novel, *nder- recognized, preventable cause of acute symptomatic seizure. Epilepsia Open 2017; 2(3):350–354.↩

-

2. Mathew T, K John S, Kamath V, Kumar R S, Jadav R, Swamy S, Adoor G, Shaji A, Nadig R, Badachi S, D Souza D, Therambil M, Sarma GRK, J Parry G. Essential oil related seizures (EORS): A multi-center prospective study on essential oils and seizures in adults. Ep*lepsy Res. 2021 Jul;173:106626. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2021.106626. Epub 2021 Mar 26. PMID: 33813360.↩

-

3. Samuels N, Finkelstein Y, Singer S R, Oberbaum M. Herbal medicine and epilepsy: Proconvulsive effects and interactions with antiepileptic drugs. Epilespia 2008; 49(3):373-380.↩

-

4. Burkhard PR, Burkhardt K, Haenggeli CA, et al. Plant-induced seizures: reappearance of an old problem. J Neurol 1999;246:667–670.↩

-

5. Tyler A. Bahr, Damian Rodriguez, Cody Beaumont, Kathryn Allred. The Effects of Various Essential Oils on Epilepsy and Acute Seizure: A Systematic Review. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2019; https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/6216745↩

-

6. Mathew T, John SK. An unsuspected and unrecognized cause of medication overuse headache in a chronic migraineur— essential oil-related medication overuse headache: A case report. Cephalalgia Reports. January 2020. doi:10.1177/2515816319897*54↩

-

7. Mathew T, John SK, Javali MV. Essential oils and cluster headache: insights from two cases. BMJ Case Rep. 2021 Aug 9;14(8):e243812. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2021- 243812. PMID:34373243; PMCID: PMC8354251.↩

Issue: Volume 5, Issue 1

Family Medicine: Transforming the Dying Art of Listenin* in Clinical Practice

Dr Prathamesh S Sawan* (Co-Founder & Executive Director: AVEKSHA Home Based Primary Care, PCMH Restore Pvt Ltd)

Being in our busy and buzzing clinical practice, many of us these days have lost the art of listening in everyday clinical decision making. I was reading up this morning on what is different in us (as Family Practitioners) listening to patients and some other doctors doing the same in their own settings. And came up across Deeya Khan and her documentary - White Right: Meeting The Enemy that talks about a story of a Muslim woman living in the UK, trolled by white supremacist to the point where police got involved because her life was at risk. They even asked her to stay away from open windows, that’s how bad it got.

The way she responded was to travel to the United States to meet the white supremacist with her camera gea* and gives them a safe space to feel heard (basically they all wanted he* off the planet, but she w*nted to hear them out). As the conversation goes ahead they feel heard and start trusting her and become friendly with her. The story continues

where they are able to open their eyes or find solutions even in the extreme conditions and change themselves just by being heard.

So listening is not just the act of hearing what’s spoken, but it’s the act of understanding themeaning behind the words. With the story above I feel li*tening can be of two types.

-

1* W*en people say you are not listening, most of the times people repeat their words what they have heard (congratulations it’s our ears that are working* this is “The Act of Listening”

-

2. “The *rt of Listening” is to create an environment (safe space) in which the other person “feels heard”. People or if we ourselves are in their place we don’t want to know they or *e have been heard, but they truly want to feel heard/seen/felt and it’s a learnable and pra*ticable skill.

It can be as simple as creating a safe space to empty the bucket (as this documentary demonstrates - once the person feels like they have completely said everything, then they are more apt to listen to you, but usually we tend to defend or litigate or interrupt or find flaws in logics as we know we are imperfect and we choose the speak the wrong words various times and the conversation spirals down on what we meant and what someone interpreted) or as simple as replacing judgement with curiosity. Another inspiring talk was by D*sha Oberoi (RJ; Hear her most mornings on the radio while driving through the traffic in Bangalore) on TEDx where she demonstrates different sounds *nd navigates people to appreciate the beauty of it. The part on “Indian Blind Cricket Team” was fascinating.

There are these 2 forms of listening I came across in my reading, and learning more on how can I or anyone embrace it into their daily living.

It’s now been ~3 years of me practicing as a part of Family Medicine team. In addition, to being privileged to experience several Family Practice settings across t*e country. I believe the art of listening is one of the major component that drives us (as Family

Practitioners) and keeps us going as an entire team. No matter the doctor seeing one patie*t an hour or 15 patients an hour or 150 patients a day, just listening to them and seeing a smile on the patient or families is beyond words. Incorporating this art in our everyday practice can minimise several unnecessary interventions (Investigations, Drugs, Procedures etc) and enhance their quality of daily living.

This is one of the major component to our patients/family relationships and trust (going generations) in family practice. I believe there are several of us practicing with *his art of listening almost every day to touch and transforming life of many com*unities.

References

Deeyah Kha*: Solidarity doesn’t cost anything (TEDx); Available at: https:/*youtube.com/watch? v=3zhYY4KQRX8

Disha Oberoi: Dying Art of Listening (TEDx); *vailable at: https://youtube.com/watch? v=mkGvy2QcG6Y

Issue: Volume 5, Issue 1

Vasodilators in clinical day to day practice

Dr L Padma (MBBS, MD, Dip. in Diabetology, Practical Cardiology and Geriatric Care)

Vasodilators *re drugs which are useful in the management *f hypertension, angina, heart failure, MI, preeclampsia, hypertensive emergencies etc.

The different classes of vasodilators used in current clinical practice has different actions on the coronary arteries and peripheral vasculature on both arteries and veins. Vasodilators more commonly affect the arteries but some vasodilators such as nitro- glycerine can affect the venous sy*tem predominantly.

Drugs

|

Directly |

Nitrates |

|

|

acting |

Venous |

(GTN and |

|

vasodilators |

Nitroglycerin) |

|

Arterial

CCB (DHP like Amlodipine and non-DHP like Verapamil)

Minoxidil,

Diazoxide

Prazosin

Drugs

Hydralazine

Mixed A*E inhibitors

ARB

Sodium

Nitroprusside

Beta 2 receptor agonist

Salbutamol

Terbutaline

|

Centrally acting Alpha |

Clonidine, |

|

2 receptor agonist |

Methyldopa |

|

Endothelin |

|

|

re*eptor |

Bosentan, |

|

Ambrisentan |

|

|

antagonists |

|

|

Beta Blockers with Nitric |

Bisoprolol, |

|

Oxide vasodilatation |

Nebivolol |

Clinical Pearls

-

1. Educate the patient about adverse effects

-

2. Importance of taking their vasodilator medication as prescribed

-

3. Under treatment or non compliance can cause severe hypertension and complications which are preventable

-

4. Ask the patient to inform if they have missed or want to stop the treatment

-

5. Educate LSM, plant based eating habits, 10,000 steps per day aerobic excercises, and avoid smoking, alcohol and recreational drugs

-

6. Cli*ical pharmacologist should assist in selection, dosing, *edication reconcil*ation and patient education

Issue: Volume 5, Issue 1

An Alternative System of Health Care Services in India : Some General Considerations

J. *. Naik (5 September 1907 - 30 August 1981; Educator; Thinker, writer, insp*rer, organizer, and administrator)

*his is the transcript of The fourth Sir Lakshman*wami Mudliar Oration delivered at the Sixteenth Annual Conference of the All India Association for the Advancement of Medical Education, at Chandigarh on Saturday, 12 March, 1977. It is being republished here for archival and wider dissemination from t*e copy of the Bul*etin of the IIE available in archive.org here.

The Search for an Alternative

I attach great importance to the word ‘alternative’ in the theme of this oration. Let me, therefore, explain in some detail what I have in mind.

When we became free, we decided to expand and improve the health services of the country as one part of a comprehensive package of *rogrammes then undertaken to raise the standards of living of the people.

Our approach to the problem, however, was rather simplistic. We adopted the western model of health services which, we thought, was ideally suited for our country. It may be pointed out that our doctors were then being trained in institutions which maintained standards comparable to those in England and thus got an automatic right to practice or serve in the U.K. The basic emphasis in this model was on the adoption of the latest medical technology developed in the West and to make it available to the people of this country through,

-

— the expansion of the bureaucratic machinery of the medical and public health departments,

-

— the expansion of the institutions of medical education to train the agents required for the delivery of health care (such as doctors or nurses),

-

— the creation of the necessary infrastructure needed for the purpose from the big hospitals in metropolitan cities to the primary health centres and dispensaries in rural areas, and

-

— the indigenous production of the essential drugs and chemicals required.

There is *o doubt that we have achieved a good deal during the last 30 years if judged by the ta*gets we thus set before ourselves. There is now a huge Minist*y of Health and Family Planning at the Centre and large departments of public health and medical services in the States. The doctor still remains the principal agent of health care and there has inevitably been a concentration on his training. As against 15 medical colleges with an *dmission capacity of about 1,200 per year in 1947, we now have 106 colleges with an admission capacity of about 12,500 per annum. The standards of training were also ‘upgraded’ with the abolition of the shorter l*cenciate course and the introduction of a uniform course of 4½ years (after 12 years of schooling) for the first medical degree. The facilities for training other functionaries — whose categories have greatly multiplied - were also increased substantially so that we are not far from the norms proposed by the Bhore Committee. A huge infrastructure of hospitals, Primary Health Centres and their subcentres, and dispensaries has also been built up. The pharmaceutical industry has been developed almost from a scratch. It now produc*s several life-saving drugs and it* output has increased from about Rs. 10 crores a year in 1947 to about Rs. 105 crores a year at present. There has a*so been immense

progress in the control of communicable diseases such as cholera, malaria and small- pox. That there is considerable impr*vement in the health status of the people due t* all these measures, is established by three main indices, viz., the increase in life expectancy from about 32 years in 1947 to about 52 years at present, the fall in death rate from about 27.4 per thousand in 1947 to about 11.3 per thousand at present, and the decline in infant mortality from about 160 per thousand live births in 1947 to about 125 per thousand live births at present.

Impressive as these achievements are — and we have every right to be proud of them — it is also realized that our failures are even more glaring For instance, we have found that t*e present system pro*ides health care services mostly in the urban areas and for well-to-do people *nd that it does not reach t*e poor people in rural areas and urban slums. The funds required to extend these services to these excluded groups will be almost astronomically large and there is no possibility of getting them within the foreseeable future. There is considerable dissatisfaction about the education of doctors. We are also not sure of what kind of a doctor we need, how to train him, and even more importantly, how to harness him to the service of the rural areas or poor people. The same can be said of other functionaries as well. The infrastructure we have built is also mostly urban and beyond a few pilot experiments - whose value and capability for generalization are still in question — we do not have clear ideas about the infrastructure and health care delivery agents needed for

ru*al areas. The system is still over-weighted in favour of curative programmes in spite of the clear conviction that, in our present situation, it is the preventive, socio-economic and educational aspects of health care systems that are the most significant. What is even more important, we are no longer sure that the western model we adopted is really suited to us, especially as its basic premises are now being challenged in the West itself by thinkers like Ivan Illich. We hav* also realized that no bureaucracy, however large and efficient, can be a substitute for the active involvement and education of the people in programmes of health improvement. In short, a*ter thirty years of development of health services, we find our*elves in the position of a traveller who sets out on a long journey, and even before he has travelled about three- tenths of the distance to his goal, finds that his purse has been stolen, his car has developed serious trouble and grave doubts h*ve arisen even abqpt *he correctness of the route he had decided to follow.

Therefore, I find a qualitative difference in the situation in the last five year*. Earlier, the assumption at least was that we are on the right track and that all that was needed was a good deal more of the same thing , and that we would be able to achieve our goals if more funds were provided and the quality of implementation were improved. Today, there is a growing awareness that what we need is not ‘more of the same’ but something ‘qualitatively different’. This is what I mean by the search of an alternative; and the Report of the Srivastava Committee is perhaps the first recognition that some alternative or

alternatives are neede*. I am very happy that we have begun to grapple with this basic problem in right earnest. I hope we will continue this effort intensively over the next two ye*rs and succeed in evolving a viable alternative, economic, health care policy which can become the core of the Sixth Five Year Plan. All that I aspire to do in this oration, with your kindness and collaboration, is to make some contribution to promote this extremely significant national endeavour.

The Basic Issues

Let me preface my detailed and concrete proposals on th* subject, which I will discuss in the following section, by a statement of what I consider to be the three basic issues of development in all sectors of our life to which the development of health care systems is no exception.

The first refers to the fundam*ntal question of the type of society we want to create in India. Mahatma Gandhi was convinced that we would have to evolve our own model of such a society in keeping with our traditions, present conditions, needs* and future aspirations. “Let the wind* from all comers of th* world blow in through the windows of my house”, he said, “but I refuse to be blown o*f my feet by any”. He also initiated a dialogue on the kind of society we must create and sustained it throughout his life. But unfortunately that dialogue disappeared with him; and we have almost equated ‘modernization’ with ‘westernization’ and are con- tent with the introduction of a pale

imitation of western models in our country. But social models cannot be so transferred, and even if they are, they will hardly be useful. There is, therefore, no escape from the earnest intellectual exercise of deciding for o*rselves the kind of society we would like to have and the model of health care systems that we should build up. In this, we may be guided by the experience of the West (or of the whole world) but not conditioned by it.

The second issue refers to the dichotomy between our professed goals which are explicitly stated and t* which generous lip sympathy is paid in season and out of season, and the hidden implicit goals which we really pursue. Before independence, we made a number of solemn ple*ges to the people of India in whose name we foug*t for political independence, viz., that we shall abolish poverty, ignorance and ill health and raise substantially *he standards of living of the masses. In the euphoria of freedom, we also embodied these assurances in the Constitution whose Preamble commit* us to the creation of a ne* social order based on freedom, equality, justice and dignity of the individual. These, therefore, are our professed goals; and the attainment of independence places our well-to-do educated classes (who now hold all the positions of power surrendered by the British authorities) on trial by challenging them to achieve these objectives. We are also compe*led to pay lip sympathy to these goals because we have adopted a system of parliamentary democracy which forces us to solicit the votes of the people and because we find it convenient and easy to do so on these populist slogans. But the achievement of

these goals is not an easy thing and it is also not in our immediate self-interest to do so. We therefore, adopt hidden and implied goals of pursuing our own class-interest. This is understandable (but not excusable) because a ruling class rules, first and foremost, for its own benefit and only incidentally for that of oth*rs. Th*s develops a dichotomy wherein w* talk of serving the masses of people, the Daridranarayanc* of India, while in reality we are more busy than ever in aggrandizem*nt for the benefit of our own classes. In fact, we have conve*ted this very dichotomy into a fine art so that, today, the best and the quickest way to become rich and powerful is to follow in the footst*ps of the Mahatma and to offer one’s life to the service of the Daridranarayana . It is necessary that we abandon this double-think and double-talk and devote ourselves in all earnestness to create an egalitarian society in India.

The third issue refers to the first steps and the pro*es* through which this egalitarian transformation can be brought about. When it comes to the discussion of an egalitarian and more just internat*onal economic order, we lo*e no time in declaring that no such transformation is possible unless the rich nations first cut d*wn their artificially inflated standards of living (which are not good for them, either) and that we must accept a ‘mini-max’ philosophy under whic* no one gets less than what is needed for decent human existence just as no one is allowed to have an affluence beyond a certain level which also degrades. Exactly the same principle applies to the national situation also. But here we want to proceed on the

assumption that the maintenance and continuous levelling up of the standards of living of the well-to-do must have the first priority on all development plans and that the programme of providing even the minimum levels of living for the underprivileged and the poor should be attempted to the extent possible after the demands of the well-to-do are first met. The problems of developing countries like India cannot be solved with this approach; and we must be prepared to share poverty with the people and delibera*ely and voluntarily agree to cut down our conspicuous con*um*tion, our unnecessary expenditure and our affluent ‘necessaries’ in order that the poor may have some fair deal. This, let me emphasize, is not a policy against the well-to-do classes. In fact, it is the only policy in support of their enlightened self- i*terest and the larger interests of the country as a whole. What Gandhiji meant by his doctrine of ‘trusteeship’ was the adoption of this *olicy *y the ruling classes, voluntarily and willingly.

At present, our policies are mainly directed to the borro*ing of some western model or the other and to advance the well-being of the well-to-do classes, in spite of all our populist slogans to the contrary. If the three basic shifts in policies discussed here are not made, we shall be continuing the same old class- oriented programmes ba*ed on the adoption of wrong technologies, with marginal changes w*ich will deceive none and which will achieve but little in improving the *onditions of the deprived groups. It is, therefore, obvious that out search for alternatives in health care s*stems must be

based on these three unexceptionable principles.

Linkages with Other Sectors

No system of health ca*e can be considered in isolation. For instance, the health status of a people at any given time will depend up*n several factors such as the following:-

-

— Healt* care systems are obviously related to concepts of health and disease. For instance, the health care systems in a *ociety which believes that all sickness arises from the wrath of gods or evil spirits will be different from those in a society where illness is held to arise fro* material causes which need a treatment in tangible, material terms. Similarly, the health care system in a society which believes in individual responsibility for health through proper exercise, regular habits and self-control will be different from that in a society where the individual is allowed every license and its evil res*lts are attempted to be corrected through medical or other intervention. Similarly, attitudes to pain, ageing or death a*so determine the nature of health care systems.

-

— Health care systems also depend upon ecological factors. We need pure and fresh air, good and safe drinking water, adequate drainage and proper disposal of night soil, proper housing and adequate arrangements or immunization and control of communicable diseases, if illness is to be preven*ed, and if satisfactory conditions are to be created

where we can hold the individual fully responsible for his health.

-

— Health status and hence health care systems, also depend upon social and economic factors such as the organisation of the home and family, equality or otherwise of the sexes, s*cial stratification, general conditions of work and poverty which increases proneness to disease while decreasing the capacity to combat it.

-

— Health is closely related to nutrition and depends upon such factors as the quality and adequacy of food supplies, dietary habits and concepts and culinary and food preservation practice.

-

— Health care systems are also obviously related to the technology of medicine and to our knowledge of and ability to deal with the malfunctioning of the body.

-

— Health is also closely related to the spread of education among the people because an individual’s understanding of health, his capacity to remain healthy and his ability to deal with illness are all conditional upon the level of his education. The nature of health care system in a society where every individual receives a good basic education will ther*fore be very different from that in another society where the bulk of the people is illiterate.

Some of these factor* fall within the sphere of health services and will be discussed here in some detail. Others like nutrition, poverty, or general education of the people are obviously

important but fall outside the limited scope of this oration. It is, however, obvious that a good system of health ser*ices cannot be built in isolation. It will have to be an integral part of a wider programme to improve the standards of living of the people and will have to be linked to programmes of abolishing poverty, achieving larger production and better distribution of food (including proper storage and improved dietary and culinary practices), and universal basic education. Family planning will, on the one hand, help the adoption of such an integrated approach, and on the other, it is the adoption of this comprehensive approach that will f*cilitate and promote a good programme of family planning.

Some General Condit*ons

No single individual can be expected to produce an alternative plan for the health care systems of our country. This is essentially an institutional and group task. I am, therefore, sure that you do not expect me to place *uch a plan before you. But you would be justified in expecting that I would at least place before you a few broad principles on which the alternative plans should be based and that I at least initiate a dialogue on the basis of which the preparation of such a plan (or plans) can be under*aken by appropriate groups and agencies in due course. It is precisely this that I shall attempt to do in the limited time at my disposal and place a ten-point programme before you for detailed examination.

1 . Target Groups

My first proposal in this context is that we should state, beyond any shadow of doubt, who the beneficiaries of these alternative systems of health care will be. We should also ensure that these proposed systems will not be so implemented that their benefits again go to those very groups who receive the lion's share of health care under the existing system.

Our developmental experience in the last thirty years shows that we *ave often gone wrong on both these counts. Several of our schemes of production (e.g. cocoa cola, canned or readymade foods, cosmetics, automobiles, cigarettes or superfine cloth) were meant to produce not the essential basic consumer goods required by the masses but the luxury and semi-luxury goods needed by the well-to-do classes. The largest beneficiaries of the development of scie*ce and technology and of our industrial development based on the concept of import- substitution, have, therefore, been the middle and the u*per classes and not the masses of the people. On the other hand, several schemes which were originally planned with the object of helping the poor and deprived groups were so distorted in implementation that their benefits also went to the well-to-do. For instan*e, many a scheme of helping the Adivasis or landless labourers through employme*t or subsidies resulted merely in passing fun*s to the money-lender or rich peasant who exploited the Adivasi or *andless labourer. The fishing industry in Kerala developed with Norwegian collaboration was

originally intended to improve the diets of poor fishermen. But when it adopted high technology, it naturally wished to make adequate profits and with this objective in view, it concentrated on catching prawns. While these prawns continued to be eaten in Tokyo, Paris, London, Bombay, or *el*i and the industry made huge profits, the diet of the poor fishermen (wh*m the scheme was to benefit) continued to be the same or even became worse.

Such distortions were found within the he*lth care services as well. If contributory health insurance schemes were to be introduced on a selective basis, the Central Government Employees are certainly not the most eligible group of citizens to be covered first under the scheme which involves a heavy subsidy. Even within the scheme, the per capita expenditure on the senior officers (deputy-secretary and above) is much larger than that on the class IV employees. The same can be said of all the infrastructure of big hospitals and super- specialities which benefit largely the well-to- do. We expanded the facilities for the training of doctors on the plea that they are needed for rural areas. But our actual experience is that the majority of the doctors we train go abroad or settle down in urban areas. The trained A.N.M. attached to the Community Development Block was meant to help the poor families. But she has actually become handmaiden to the rich and powerful rural elite. Similarly, several schemes meant specifically for rural areas and the poorer people have made no headway in practice. For instance, the programme of training village Dais has co*tinued to languish; and as

Professor Banerji points out in his ad- mirable booklet on Formulating an Alternative Rural Health Care System for India (pp. 7-8) “In 1963, a Government of India Committee recommended that rural populations may be provided integrated health and family planning services through male a*d female

multipurpose workers. But the, clash of

interests of malaria and family planning campaigns soon led to the reversion to unipurposes workers. In 1973, yet another committee revived the idea of providing integrated health and family planning services

through multipurpose workers. This time

also the prospect of effective implementation of the scheme does not appear to be very bright. Earlier, there had been at least two more efforts, both similarly abortive, to develop alternative health strategies. One, the so-called Master Plan of Health Services envisaged (in 1970) more incentives to physicians, establishment of 25-bed hospitals and use of mobile dispensaries for remote and

difficu*t rural areas. The other, apparently

inspired by the institution of Barefoot Doctors of China, was to mobilise an estimated 200,000 Registered Medical

Practitioners of different systems of medicine as “Peasant Physicians” to serve as rural

health workers”

D*ring the British period, our health care systems were based on the idea of making modern medical and health technology available to a class of people who were well- to-do and mostly urban. In spite of all that we have said to the contrary, the same policy has been continued substantially during the last thirty years. Eve* today, about 70 per cent, of

the people do not have access to even the most elementary health care services. This cannot be allowed to continue; and one acid test of all proposals for alternatives should be that they should really benefit, in planning as well as in implementation, the poor and deprived people living in rural areas or urban slums. The talisman that Gandhiji suggested is very relevant in this context; whenever one has to decid* the priority or desirability of a plan, one must always relat* it to the extent to which it will actually benefit the poorest and the lowliest of the low.

2. Emphasis on Preventive and Protective Aspects

My second proposal is that the new health care systems we propose to deve*op as alternatives should move away from the over- emphasis which the existing systems place on mere curati*e measures and must place a much greater emphasis on preventive and protective measures to which a large bulk of the available resources should be devoted. For instance, our achievements in making better nutrition available to the people are by no means impressive; and even tod*y, very large se*tions of people go without adequate food. It is true that the total available food supply has increased. But the production of coarse foodgrains, on which the poor people mostly live, has not kept pace with the increase in the numbers of the poor. We have hardly any system of public *ood distribution in rural areas (outside Kerala). Nor have we made any sizable impact on the capacity of the poor to buy food in the market. Provision

of protected water supply has b*en made for four-fifths of the urban population but nearly 120,000 villages with a po*ulation of more than 60 million people do not still have even the most elementary water-supply system. Sewerage exists only fo* 40 per cent of the urban population. Most medium and small towns have no sewerage systems and in the rur*l areas, the programmes of drainage and sewerage are nowhere in sight. It is true that considerable progress has been made in the control of cholera, small-pox and malaria. These gains need to be conserved and developed further. But the prevalence of infections in general and *ntestinal infections in particular is still large; and in several areas, a vicious circle has already been established; infection leading to mal*utrition and malnutrition in its turn leading to increased proneness to infection. It may be asserted without fear of contradicti*n that under the present conditions in India, protective and preventive measures are even more important than curative ones. The alternative plans we propose to develop must, therefore, lay a greater emphasis on them.

3. Choice of Technology

The third basic issue in which the alternative plan* blaze a new trail is that of health and medical technology. The policy adopted so far, and this is true of all spheres of life including health, has been to consid*r technology as sacrosanct and above all laws. We have always tried to introduce in India the most highly developed technology the world has discovered on the assumption that our people should have nothing less than the

absolutely first-rate available anywhere else in the world. As the over-riding principles in the choice of te*hnology are its modernity and advanced character (and not suitability to the people), we generally expect the people to adjust themselves to technology rather than the other way round. These policies, I am sorry to say, have been proved to be wrong and counter-produc*ive. It is now universally agreed that technology cannot be an end in itself. It can *nly be a means to an end, viz,, the welfare and growth of the people so that we must choose a technology best suited to the interests of the people and not expect the people to adjust themselves to the technology. Secondly, we have now learnt that the choice of technology is extremely crucial because it affects priorities, target groups, investment levels, and the character of the delivery agents. A higher level of technology requires a larger investment; it needs a more highly trained and sophisticated delivery agent; and its benefits tend to accrue to a smaller and more pr*vileged social group. It is, therefore, our decision to adopt the *est health and medic*l technology available *n th* world that has *ed to the creation of the present system of health care services in the coun*ry, oriented to the well-to-do classes *nd *hich

is in the words of Professor V. Ramalingaswamy, ove*-centralized, over- expensive, over-professionalized, over- urbanized and over-modified.

The question, therefore, is whether it is always necessary fo* us to ‘soar’ upwards in the technological ladder as we have done. That this is not absolutely essential is evident from several important experiments. The

Chinese developed a workable system of health care oriented to the people, with the help of barefoot doctors. Cuba did an equally creditable job with unsophisticated personnel. Garl Taylor trained il*iterate Muslim women in Noakhali *o perform tubectomy. In our own country. Dr. Raj Arole at Jamkhed has trained illiterate village women to take care of 70 per cent of the common illnesses of the local community. Dr. C. Gopalan is prepared to train the village teachers for the delivery of curative services for day-to-day illnesses. These illustrations lead to two conclusions. The first is that there are, as Wordsworth has pointed out, two types of the wise — those that ‘soar’ upwards to the stars and those that ‘roam’ far and wide on this our earth. We tried to ‘soar’ and the Chinese decided to ‘roam’. Perhaps it would be more correct to say that this is not really a* ‘either-or’ issue and we must have both types of the wise, those who soar and those who roam, in a proper combination and a fruitful or*anisation dictated by the needs of the country. This is what the Chinese seem to have done while we *ecided only to soar. *econdly, it appears that even high technology lends itself to two kinds of treatment. We can mystify it and restrict its use to only a few highly sophisticated and professionali*ed individuals. On the other hand, we can demystify it a*d train even the unsophisticated non-professionals to handle it. The best illustration is that of the agricultural scientists who take, pride in demystifying even the highest technology and placing it in the hands of even illiterate farmers. Innovat*rs like Carl Taylor, Raj Arole and Gopalan have shown that this can

be done in the field of health services as well. Why can’t we have more of the same?

Whatever the decision on this issue may be, let us not forget one significant factor, viz., the type of health care systems we develop will depend upon our choice of technology to be adopted. What we have done in the existing health care systems is that we first introduced, in a few of our met*opolitan cities, a technology that existed in London and then tried to spread it to the ‘periphery’ where the mass of the people live. The attempt has failed and cannot succeed. Can we not instead begin with the local community and with such local technologies as already exist? This can be a real alternative. As Professor Banerji writes:

“An obv*ous framework for suggesting an alternative to the existing approach of “selling” some technology to the people will be to start with the people. This will ensure that technology is harnessed to the requirements of the people, as seen by the people themselves — i.e. technology is subordinated to the people. This alternative enjoins that technology should be taken with the people, rather than people taken with technology by “educating” them.

“Based on their way of life, i.e. on their culture, people in different communities have evolved their own way of dealing with their health problems. This concept forms the starting point, indeed the very